Updated: August, 2022

© 2022 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

The Social Thinking Methodology has evolved over the last 25+ years by continually learning from the perspectives and experiences of those we support. We believe meaningful teaching requires focused learning about the individual based on their own perspective rather than from assumptions on our part. This story gives you the opportunity to see through the eyes of someone with social learning differences (from her perspective, challenges) to better understand how difficult it can be to navigate the complex social world. It also demonstrates how easy it can be for support teams or educators to assume social knowledge and skills because a person is highly verbal or appears to understand the social world— sometimes to the detriment of their well-being. This is the life story of Belinda, a woman with significant social learning differences.

The danger of making social assumptions

On any given day we make thousands of assumptions and have very specific expectations for how we think others should behave in innumerable contexts: the driver will stop at the crosswalk when we make eye contact and not run us over; a stranger’s smile and greeting while passing on the sidewalk is not an invitation for conversation; a casual statement from a friend about getting together soon is not a definite commitment; an invitation to a wedding means we dress specially for the occasion. It’s safe to say that most of us take these assumptions for granted. As humans, most of us are hard-wired to understand how the social world works. And we make assumptions that everyone has that same understanding, which is clearly not always the case.

Welcome to Belinda’s world—a world where people assume she understands the nuances of the social world and become intolerant when her social behaviors don’t match their assumptions. Can we imagine—what it really feels like—being ignored, rejected, and even actively tormented for not intuitively understanding the ever-shifting hidden rules and expectations within the social world?

Through clinicians’ eyes: assessment summary reports for Belinda

November 2018: Psychologist

“Belinda presented as a cooperative woman of 44 years. Belinda could establish eye contact but would look down. She showed little response to praise and often showed no indication of whether she was still thinking of an answer or had finished, due to her lack of non-verbal communication. Belinda needed rule reminders on various tasks. She required longer questions to be repeated and was somewhat literal in her interpretation of language. Belinda displayed an inflexible thinking style and struggled with abstract thinking.”

March 2019: Speech Pathologist

“Belinda presents as a well-groomed, compliant, socially awkward and detached woman with obvious features aligned with her diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). When meeting Belinda for the first time, she generally did not speak unless spoken to, and her non-verbal communication behaviors appeared limited, e.g., fleeting eye contact, minimal facial expression, limited gesture, and her body posture and positioning indicated she was ‘closed off’ rather than open. I sensed that Belinda is constantly working internally to process the multi-sensory aspects of her surroundings and human interaction is an activity that does not come naturally to her and is difficult for her to process in conjunction with other environmental stimulation. Belinda appeared occasionally bewildered by and reluctant to engage in ‘small talk’ and general conversation as a means of building rapport. Belinda was observed to mainly interact in response to direct questions from me as part of the assessment interview, and I conducted my interview with Belinda in a way to minimize misunderstanding and anxiety, e.g., task-focused, with clear, direct, literal language.”

March 2019: Vineland Report (explores skills for adaptive functioning)

“The Communication domain measures how well Belinda listens and understands, expresses herself through speech, and reads and writes. Her Communication standard score is 34. This corresponds to a percentile rank of ≤ 1. This means that Belinda scored below at least 99% of the normative sample in the Communication domain. It places her in the lowest category recommended by the test authors when qualitative descriptors are useful, which are: High, Moderately High, Adequate, Moderately Low, Low.”

Belinda’s Age Equivalents in the Vineland:

Receptive: 2 years, 3 months

Expressive: 4 years, 8 months

Written: 11 years, 9 months

Through Belinda’s eyes: learning to live in a social world

Diagnosed with autism at three years old in the 1970s, Belinda had no functional language until she was eight, was not completely toilet trained until she was nine, and did not learn to read until she was fourteen. One can only imagine the sort of assumptions folks made about her and her prognosis. Yet, after many hours of speech therapy throughout childhood, Belinda now has superb “surface-level expressive language” skills, what she calls her greatest asset, but what also is a smokescreen for her deeper learning difficulties. She is quite literal in her understanding of language and misunderstands much of what is said and often doesn’t know she has misunderstood. Ironically, her language skills are simultaneously her greatest challenge.

At age 45, Belinda is well-spoken and looks professional in her suit. One might assume she is an educator or therapist—and most would expect the kind of intuitive social interaction, understanding, and behavior that comes with those assumptions. But what her language skills and appearance fail to reveal is that Belinda’s social learning system does not intuitively and easily learn social-emotional and self-regulation information. Even as a mature adult she needs to focus hard to figure things out, and many social aspects of the world remain a mystery. She also continues to struggle with sensory processing, coping with change and noise; crowds can still overwhelm her. Stress can also be a minefield for Belinda if she isn’t ever mindful to avoid or prepare for situations. As a result, she must discover, study, practice, and learn every social nuance for myriad contexts throughout a day that most neurotypical adults—even children—know intuitively and perform almost effortlessly with minimal active awareness, in the same way people learn to drive cars or ride skateboards and bicycles.

An act as seemingly simple as walking on a sidewalk in an urban setting teems with hazards and unknowns for Belinda. Contrary to what she’s been told, she knows it’s not anxiety that causes her to stop at every driveway to scan for cars or prevents her from crossing the street. It’s sheer bafflement. What if a car is exiting or entering the driveway? How can one possibly know what the driver is going to do next? Belinda was 30 years old when someone finally showed her that she needn’t look down at her feet while walking to avoid tripping but could instead look up and see what was ahead of her. It had never once occurred to her that she could predict what might happen next based on what she saw before her.

Belinda knows but she doesn’t know

Belinda, herself, is amazed at what she knows but doesn’t know. For example, she knows she has a physical vision impairment that is not correctable with glasses and has known this all her life. At school she had to be in the front row or, in some cases, sit at a special desk placed in the front of the room to see the screen or board. What she understood was that her vision differs from others. But she always wondered why the letters on street signs were so small that no one could read them, or why the menu boards in restaurants were written in such a tiny script that no one could possibly make out what they said. Not until a year ago did she realize that most everyone else can, in fact, read those signs. She recently figured out that a common typical social expectation would be for her to ask for assistance in reading the signs or menu boards or whatever she cannot see. Not only does Belinda not perceive that she often needs assistance in myriad ways, but most people around her would never conceive that she does not know how to formulate the words and non-verbal language to ask for help when she does recognize her need. Instead, we the social judges would automatically assume that she did not want or need assistance because of our assumptions based on her appearance.

Throughout her life, Belinda has been told repeatedly that she yells at people, yet she never understood why people were angry or put off by her yelling. She assumed that when people didn’t answer or respond to something she said, it was because they didn’t hear her—so, logically, she raised her voice to ensure that they heard. People assumed that she knew what a shoulder shrug, a dismissive wave, raised eyebrows, a facial expression, or even leaving the room meant. She was never taught this information, yet somehow, she was expected to know.

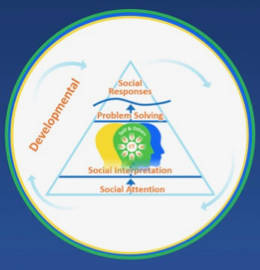

Instead, Belinda was taught rote social behaviors: look at people’s eyes when you speak with them, stand near people if you want to be included in the group, write a script for what you want to say on the telephone, dress for the weather. What Belinda wasn’t learning was why people bother to use these behaviors. She had yet to learn and internalize that communication and sharing space with others evolve from an intricate process of socially attending to take perspective within a specific context, which would help her interpret others’ intentions and how they might interpret and feel about her social responses. She hadn’t been taught that this process will lead to her social problem solving to evaluate and then determine her actions and reactions. And then, the process begins all over again because social landscapes shift quickly and require cognitive flexibility and emotional regulation to respond adeptly. Due to her not knowing this process for thinking socially, Belinda has suffered confusion, hurt, rejection, and abuse for decades.

Four years ago, Belinda read a passage in Why Teach Social Thinking®?, that she describes at first as incomprehensible, but then astonishing! After reading “eyeballs move,” Belinda peered into the bathroom mirror and witnessed for the very first time in over 40 years that her eyeballs do indeed move! In another critical moment of discovery, Belinda learned—despite a lifetime of pointing to smiley faces and frowny faces in an effort to recognize emotions in others and herself—that it is not the face alone that reveals emotions, but the context in which the face or person exists. A person can cry, not just because of sadness, but can also shed tears of happiness, or cry because of chopping onions or from dust. Before that moment Belinda had never been taught or understood that one must understand context or, perhaps more importantly, how to use contextual information to interpret social information, a cornerstone of developing social competencies.

People like Belinda struggle, not only because they haven’t been taught, but because their social brains struggle to efficiently process and respond to so much nuanced social information in a short period of time. Yet, because Belinda appears “neurotypical,” the more harshly she is judged. For example, in addition to her language prowess, Belinda has terrific research skills—although by her own admission, has no idea how to organize the details and “heaps” of information in her brain once acquired. Her brain makes gathering information easy, but it makes it nearly impossible for her to sort through, organize, and summarize what she’s read. Her greatest passion is social policy, particularly around autism and disability, and to a lesser degree, trauma/child protection and homelessness, stemming from her own life experience. She understands that others may not be as passionate or knowledgeable about her topics but doesn’t know how to have conversations with people or how to evaluate what they know, want to know, or when they don’t want to talk about it anymore. So, she ends up talking at them with her wall of information, as opposed to with them. So, people tend to cut her off or talk over her. Instead of making a much-desired connection with others, she becomes dispirited by these painful and complicated interactions, so much so that she wonders, “Why even bother?”

What we learn from seeing through the eyes of this social learner

As educators, clinicians, therapists, and other types of interventionists, we constantly make assumptions about our students and clients based on their physical appearance, their age, their education, their IQ, and their language. For individuals like Belinda who struggle to interpret our abstract social world, people can be confusing and sometimes cruel. How many Belindas do you know—those students and clients who have been taught or rely on rote social behaviors, but in fact need to understand the deeper nuances of how the social world works?

What Belinda asks of us—for herself and for others with social learning differences and/or challenges—is that we try to take her perspective and understand that she is not trying to offend. She asks that instead of dismissing her out of our own discomfort, we take the time and make the effort to explain what might confuse us. Belinda asks us to see the social world through her eyes instead—without assumptions—so that she can see it through ours. It is only then that we can all work together to create a community that respects each other’s differences and learns and benefits from each other’s strengths.